File storage under PCI DSS / PCI SSF - avoiding the Clear Text Window

File-based workflows are an essential part of today's payment processing. It’s normal to store transaction data to local disks as DCF imports/exports, Black/White list loads, BIN list loads, produce Mastercard / Visa clearing files such as IPM, Base2 and MBF, and generate operational extracts and reports along the way.

Historically, the pattern has been: have clear text files locally → rely on DMZ / host controls / full-disk encryption → encrypt/archive later → distribute/consume.

That approach is now increasingly hard to defend under PCI DSS v4.x, not because file workflows are inherently wrong, but because any local clear text storage creates an avoidable exposure window. In today's cloud-native deployments that window spreads across more surfaces (ephemeral volumes, node re-scheduling, snapshots, backups, and log pipelines), making it harder to control and harder to prove controls are appropriate.

PCI’s core framing: if it’s stored, it must be protected- and stored includes files, backups, and logs

PCI DSS Requirement 3 explicitly targets stored account data. It calls out that PAN must be secured wherever it is stored and defines approved approaches to render it unreadable (tokenization, truncation, strong cryptography, etc.).

Two details matter for real-world platforms:

1/ Storage includes flat files and non-primary locations

PCI DSS makes it explicit that this applies not only to databases, but to all flat files (including text files/spreadsheets), and to non-primary storage such as backups and logs (audit, exception, troubleshooting).

2/Full-disk encryption is not a get-out-of-jail card

PCI DSS guidance explains why disk/partition encryption is often not appropriate as the sole protection for stored PANs on systems that transparently decrypt after user authentication, and it restricts when disk-level encryption can be used on non-removable media (it typically must be paired with a mechanism that meets Requirement 3.5.1, such as data-level encryption).

This is a big deal for drop it to disk and deal with it later architectures: it’s no longer enough to say the box is encrypted if the system behaviour effectively makes PANs readable to anyone who obtains legitimate access to the host/session.

Temporary files are not prohibited - but that’s not the same as business-as-usual spooling

PCI DSS does include an important nuance: the requirement does not preclude the use of temporary files containing clear text PAN while encrypting and decrypting PAN. The practical problem is what we agree temporary means. Even if a clear text file exists only for the duration of an encrypt/decrypt step, you’re relying on the correct deletion behaviour on the underlying storage stack to honour that intent.

In modern environments that’s hard to guarantee, file systems use journaling for their operation, SSDs remap blocks, storage is layered and replicated, and backup/snapshot systems can capture data mid-flight. The potential that a temporary clear text file can become a durable artifact is high and having the correct processes in place and proving to a QSA that they work is complex and time consuming.

PCI DSS acknowledges that cryptographic operations may involve transient handling, not that clear text file spools are an acceptable long-running integration pattern. The difference is intent and control:

- Transient crypto handling: short-lived, tightly scoped, not discoverable/consumable as an integration artifact

- Operational clear text spooling: intentionally persisted, often discoverable, often backed up/snapshotted, and routinely accessed by ops tooling

PCI Secure Software pushes the same direction - as a software responsibility. PCI Secure Software Standard (previously SSF) frames this as a software design obligation:

Strong cryptography is used to protect sensitive assets output from the software using individual data-level and/or session-level protection

PCI Secure Software also emphasizes retention and deletion: Only stored until it is no longer necessary, at which time it is securely deleted, else it is rendered unrecoverable.

So where should these files live?

Real payment platforms still need file-like artifacts:

- Ingress: DCF transaction imports and exports, Black/White lists

- Egress: clearing outputs (IPM, Base2, MBF), plus downstream extracts and reports

The pragmatic answer is to avoid the Clear Text Window completely - encrypt on ingress, persist only ciphertext, decrypt only on authorized egress. That gives you the operational benefits of file workflows without expanding your PCI scope to every host that happens to store or touch those files.

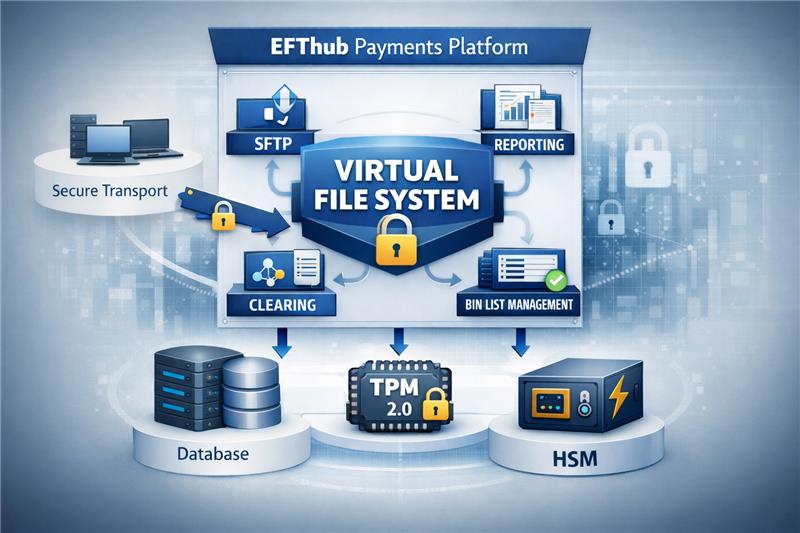

EFThub’s approach: Virtual File System, backed by encrypted database storage

This is exactly the gap EFThub’s Virtual File System (VFS) is designed to close.

At a high level:

- Applications still write a file and read a file (familiar operational semantics)

- The VFS encrypts content as it is written (streaming), so you don’t produce any clear text artifacts on local disk

- The encrypted payload is stored centrally (database-backed), where access can be controlled and audited

- Retrieval/decryption happens only on explicitly authorized egress paths - for example:

- delivering Visa / Mastercard clearing files (IPM/Base2/MBF) via SFTP

- retrieving regulated extracts/reports for downstream systems from the UI

- processing imports/exports for controlled reconciliation or operational recovery

This aligns cleanly with PCI’s posture that the PAN must be secured anywhere it is stored, including flat files and log-like repositories, and avoids leaning solely on external encryption mechanisms that PCI explicitly treats as insufficient on typical servers/storage arrays when they decrypt transparently in normal operation.

The takeaway

Legacy platforms normalized “Write clear text now, Encrypt later” because there was nothing else to solve this.

PCI DSS v4.x and SSF v2.0 increasingly push toward the opposite:

Minimize storage, protect what must be stored, and make protection independent of the host environment.

Encrypt on ingress, decrypt on egress using HSM or TPM2.0 backed keys with controlled, auditable storage is one of the few patterns that keeps file-driven payment operations practical and keeps the compliance argument straightforward.